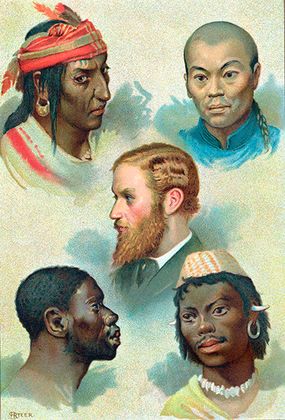

The concepts of race and ethnicity are so intertwined that it's sometimes hard to tell one from the other. Even unwound, the ideas are not as well-defined as many would present them to be.

The reason for that is simple: Yes, humans are adiverse lot. We can look distinctively different. We're seen sometimes completely differently. We come from different places (though we all, as a species, come from modern-day Ethiopia), and the groups from which we have grown — our families, our clans, our cultures, our nations — all have traveled different paths. A wide world of factors have influenced our appearance and our ways of life during thousands of years of evolution andmigration.

Advertisement

Yet all those amazingly diverse peoples don't exist in a vacuum. Over all those millennia and all those miles, we've become mixed. And our ethnic backgrounds continue to mix.

Putting us in distinct boxes with fixed labels is near impossible. Even the labels get jumbled.

"I think there's a ton of overlap [between the terms ethnicity and race]," says Douglas Hartmann, a professor of sociology at the University of Minnesota and co-author of "Ethnicity and Race: Making Identities in a Changing World" (with sociologist Stephen Cornell). "I really think it's difficult to disentangle them. And maybe even inappropriate. Because all of these categories have elements of identity, self-assertion, culture and heritage. But they also have elements of labeling, of stigma, of differential treatment, of power inequality, etc."

Still, maybe because of some innate need for order — or something more sinister — we continue to define. We identify people as this race or that ethnicity. We self-identify, too.

And so it is that these labels become blurry and, at times, inseparable.

Advertisement