Has a witch ever stolen a piece of your hair and used it to put a hex on you? Probably not. Today, such superstitions seem silly -- at least until you examine what you can accomplish with a lock of hair. You can place a suspect at the scene of a crime or find out what your employees' favorite illegal drugs are. In fact, thanks to advancements inDNAresearch, one little strand of hair can clue you in to an organism's entire biological blueprint.

Advertisement

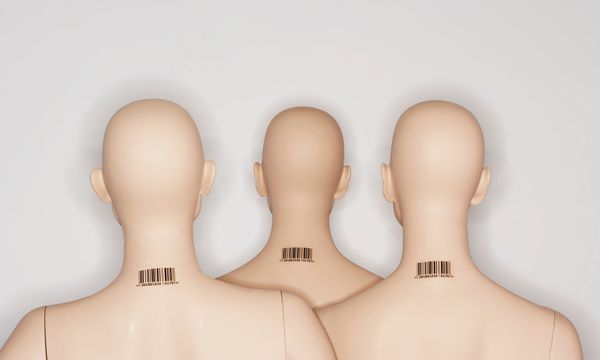

Across the world, scientists are using this knowledge to study diseases, revive extinct animal species and potentially help couples with fertility problems. And while all this is well and good, it's not really in keeping with the scheming of storybook wizards and mad scientists. How's an enterprising villain supposed to profit from any of this?

A successfulcloningprocedure would give you a genetic double of the target, minus the subject's accumulated memories and learned responses. Therefore, you couldn't very well steal a hair from Donald Trump and instantly produce a clone who could fork over access to his bank accounts. To make your fast, underhanded fortune in the cloning business, you'd need to find an established, high-paying market for genetic material. Look no farther than professional horseracing.

There's an enormous amount of money to be made in breeding the next Triple Crown winner. Take 2000 Kentucky Derby winner Fusaichi Pegasus for example. The racing stallion sold for a record $60 million following his win, and his genetic material is about as top-shelf as it gets. His stud fee is currently $150,000. Fusaichi himself is the son of $20 million Mr. Prospector, whose stud fee reached as high as $500,000 a pop [source: Forbes Magazine].

That's some pretty expensive semen. But what if you could cut out the middlemen? By stealing a few hairs from a horse like Fusaichi Pegasus, couldn't you do one better and simply produce the champion's exact genetic double?

Read the next page to find out.

Advertisement